The Situation

You are a researcher or sourcer and you need to convince your boss to make a change. So, you ask yourself . . . How can I convince the decision-maker of this change in our priorities that are best in this specific situation. And how can I avoid the selection of the priorities that would cause this initiative to fail.

Preparation

First, all decisions are a trade-off of one form or another. It’s a fact. You can look it up.

Second, the decision is being considered to address a concern, deal with an issue, or to solve a problem. Let’s define a problem as the gap between what you now have and what you want; it’s the gap, disparity, the variance, the difference, or for you whiz kids in Math, the Delta.

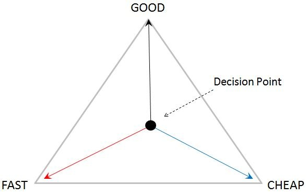

Let’s take a quick look at the model

A simple Equilateral Triangle. In the center of the triangle is a decision point. The labels at the three angles are “Good”, “Fast”, and “Cheap.” And there can be an “Arrow” signifying the direction of your organization.

The Terms

- Good: refers to quality or effectiveness, perhaps quality of hire

- Fast: refers to speed of delivery; time to deliver; perhaps time to fill

- Cheap: refers to total resources used; money, people, supplies, etc.

Rule 1

From the center decision point you can move in any single direction of your choice. Your organization can select Good, or Fast, or Cheap and achieve it almost 100% of the time. It may not be easy, but it is simple from a decision-making perspective.

Rule 2

From the center decision point you can also move in any two directions of your choice. Your organization can select Good and Fast, or Fast and Cheap, or Cheap and Good. This decision is rarely easy, nor simple from a decision-making perspective, yet it is still doable. But then there’s Rule 3.

Rule 3

Whenever you move toward one of Good, Fast, or Cheap you also move away from the other two. When you move toward any two of Good, Fast, or Cheap you then move even more dramatically away from the third. That is your problem. If you want it Good and Fast, then what won’t it be? It will take a lot of resources, perhaps even scarce resources; it won’t be Cheap. And if you want it Good and Cheap, then what won’t it be? It will take a lot of time, perhaps even more time than you can allow. It won’t be Fast. It can’t be. And lastly, if you want it Cheap and Fast, then what won’t it be? Remember the old “How bad do you want it?” joke? It just can’t have a quality focus.

You boss (or your client) in the corner office, is good, and smart, and committed. But your boss doesn’t know about the Good-Fast-Cheap Model. And so, it’s not the boss’s fault, but they expect it all, they ask for it all, and they demand it all. They want it Good, Fast, and Cheap. I say again, it is not their fault.

They were not taught in college about the Good-Fast-Cheap Model. It wasn’t in any company training or learning sessions either. They simply don’t address identifying conceptually flawed points of view. [A brief historical note; the only client, teacher, and student that I can recall teaching this idea was when Philip II of Macedon hired Aristotle to tutor his son Alexander in about the year 346 BC.]

Conclusion

It is your responsibility to teach your boss or your client why they can’t have it all. It is not their responsibility to know it already; that is for you, as the enlightened business consultant, to do.

this article originally appeared in the June 2008 issue of The Source.